Create an SSL Certificate on Apache for CentOS

hostname set-hostname <name server>

Step 1 — Installing mod_ssl

In order to set up the self-signed certificate, you first have to be sure that mod_ssl, an Apache module that provides support for SSL encryption, is installed on the server. You can install mod_ssl with the yum command:

sudo yum install mod_ssl openssl

Copy

The module will automatically be enabled during installation, and Apache will be able to start using an SSL certificate after it is restarted. You don’t need to take any additional steps for mod_ssl to be ready for use.

Step 2 — Creating a New Certificate

Now that Apache is ready to use encryption, you can move on to generating a new SSL certificate. TLS/SSL works by using a combination of a public certificate and a private key. The SSL key is kept secret on the server. It is used to encrypt content sent to clients. The SSL certificate is publicly shared with anyone requesting the content. It can be used to decrypt the content signed by the associated SSL key.

The /etc/ssl/certs directory, which can be used to hold the public certificate, should already exist on the server. You will need to create an /etc/ssl/private directory as well, to hold the private key file. Since the secrecy of this key is essential for security, it’s important to lock down the permissions to prevent unauthorized access:

sudo mkdir /etc/ssl/private

sudo chmod 700 /etc/ssl/private

Copy

Now, you can create a self-signed key and certificate pair with OpenSSL in a single command by typing:

sudo openssl req -x509 -nodes -days 365 -newkey rsa:2048 -keyout /etc/ssl/private/apache-selfsigned.key -out /etc/ssl/certs/apache-selfsigned.crt

Copy

You will be asked a series of questions. Before going over that, let’s take a look at what is happening in the command:

- openssl: This is the basic command line tool for creating and managing OpenSSL certificates, keys, and other files.

- req: This subcommand specifies that you want to use X.509 certificate signing request (CSR) management. The “X.509” is a public key infrastructure standard that SSL and TLS adheres to for its key and certificate management. You want to create a new X.509 cert, so you are using this subcommand.

- -x509: This further modifies the previous subcommand by telling the utility that you want to make a self-signed certificate instead of generating a certificate signing request, as would normally happen.

- -nodes: This tells OpenSSL to skip the option to secure your certificate with a passphrase. You need Apache to be able to read the file, without user intervention, when the server starts up. A passphrase would prevent this from happening because you would have to enter it after every restart.

- -days 365: This option sets the length of time that the certificate will be considered valid. You set it for one year here.

- -newkey rsa:2048: This specifies that you want to generate a new certificate and a new key at the same time. You did not create the key that is required to sign the certificate in a previous step, so you need to create it along with the certificate. The

rsa:2048portion tells it to make an RSA key that is 2048 bits long. - -keyout: This line tells OpenSSL where to place the generated private key file that you are creating.

- -out: This tells OpenSSL where to place the certificate that you are creating.

As stated above, these options will create both a key file and a certificate. You will be asked a few questions about your server in order to embed the information correctly in the certificate.

Fill out the prompts appropriately.

Note: It is important that you enter your domain name or your server’s public IP address when you’re prompted for the Common Name (e.g. server FQDN or YOUR name). The value here should match how your users access your server.

The entirety of the prompts will look something like this:

OutputCountry Name (2 letter code) [XX]:US

State or Province Name (full name) []:Example

Locality Name (eg, city) [Default City]:Example

Organization Name (eg, company) [Default Company Ltd]:Example Inc

Organizational Unit Name (eg, section) []:Example Dept

Common Name (eg, your name or your server's hostname) []:your_domain_or_ip

Email Address []:webmaster@example.com

Both of the files you created will be placed in the appropriate subdirectories of the /etc/ssl directory.

As you are using OpenSSL, you should also create a strong Diffie-Hellman group, which is used in negotiating Perfect Forward Secrecy with clients.

You can do this by typing:

sudo openssl dhparam -out /etc/ssl/certs/dhparam.pem 2048

Copy

This may take a few minutes, but when it’s done you will have a strong DH group at /etc/ssl/certs/dhparam.pem that you can use in your configuration.

Step 3 — Setting Up the Certificate

You now have all of the required components of the finished interface. The next thing to do is to set up the virtual hosts to display the new certificate.

Open a new file in the /etc/httpd/conf.d directory:

sudo vi /etc/httpd/conf.d/your_domain_or_ip.conf

Copy

Paste in the following minimal VirtualHost configuration:

/etc/httpd/conf.d/your_domain_or_ip.conf

<VirtualHost *:443>

ServerName your_domain_or_ip

DocumentRoot /var/www/html

SSLEngine on

SSLCertificateFile /etc/ssl/certs/apache-selfsigned.crt

SSLCertificateKeyFile /etc/ssl/private/apache-selfsigned.key

</VirtualHost>

Be sure to update the ServerName line to however you intend to address your server. This can be a hostname, full domain name, or an IP address. Make sure whatever you choose matches the Common Name you chose when making the certificate.

Setting Up Secure SSL Parameters

Next, you will add some additional SSL options that will increase your site’s security. The options you will use are recommendations from Cipherlist.eu. This site is designed to provide easy-to-consume encryption settings for popular software.

Note: The default suggested settings on Cipherlist.eu offer strong security. Sometimes, this comes at the cost of greater client compatibility. If you need to support older clients, there is an alternative list that can be accessed by clicking on the link labeled “Yes, give me a ciphersuite that works with legacy / old software.”

The compatibility list can be used instead of the default suggestions in the configuration above between the two comment blocks. The choice of which config you use will depend largely on what you need to support.

There are a few pieces of the configuration that you may wish to modify. First, you can add your preferred DNS resolver for upstream requests to the resolver directive. You used Google’s for this guide, but you can change this if you have other preferences.

Finally, you should take a moment to read up on HTTP Strict Transport Security, or HSTS, and specifically about the “preload” functionality. Preloading HSTS provides increased security, but can have far reaching consequences if accidentally enabled or enabled incorrectly. In this guide, you will not preload the settings, but you can modify that if you are sure you understand the implications.

The other changes you will make are to remove +TLSv1.3 and comment out the SSLSessionTickets and SSLOpenSSLConfCmd directives, since these aren’t available in the version of Apache shipped with CentOS 7.

Paste in the settings from the site after the end of the VirtualHost block:

/etc/httpd/conf.d/your_domain_or_ip.conf

. . .

</VirtualHost>

. . .

# Begin copied text

# from https://cipherli.st/

SSLCipherSuite EECDH+AESGCM:EDH+AESGCM

# Requires Apache 2.4.36 & OpenSSL 1.1.1

SSLProtocol -all +TLSv1.2

# SSLOpenSSLConfCmd Curves X25519:secp521r1:secp384r1:prime256v1

# Older versions

# SSLProtocol All -SSLv2 -SSLv3 -TLSv1 -TLSv1.1

SSLHonorCipherOrder On

# Disable preloading HSTS for now. You can use the commented out header line that includes

# the "preload" directive if you understand the implications.

#Header always set Strict-Transport-Security "max-age=63072000; includeSubdomains; preload"

Header always set Strict-Transport-Security "max-age=63072000; includeSubdomains"

# Requires Apache >= 2.4

SSLCompression off

SSLUseStapling on

SSLStaplingCache "shmcb:logs/stapling-cache(150000)"

# Requires Apache >= 2.4.11

# SSLSessionTickets Off

When you are finished making these changes, you can save and close the file.

Creating a Redirect from HTTP to HTTPS (Optional)

As it stands now, the server will provide both unencrypted HTTP and encrypted HTTPS traffic. For better security, it is recommended in most cases to redirect HTTP to HTTPS automatically. If you do not want or need this functionality, you can safely skip this section.

To redirect all traffic to be SSL encrypted, create and open a file ending in .conf in the /etc/httpd/conf.d directory:

sudo vi /etc/httpd/conf.d/non-ssl.conf

Copy

Inside, create a VirtualHost block to match requests on port 80. Inside, use the ServerName directive to again match your domain name or IP address. Then, use Redirect to match any requests and send them to the SSL VirtualHost. Make sure to include the trailing slash:

/etc/httpd/conf.d/non-ssl.conf

<VirtualHost *:80>

ServerName your_domain_or_ip

Redirect "/" "https://your_domain_or_ip/"

</VirtualHost>

Save and close this file when you are finished.

Step 4 — Applying Apache Configuration Changes

By now, you have created an SSL certificate and configured your web server to apply it to your site. To apply all of these changes and start using your SSL encryption, you can restart the Apache server to reload its configurations and modules.

First, check your configuration file for syntax errors by typing:

sudo apachectl configtest

Copy

As long as the output ends with Syntax OK, you are safe to continue. If this is not part of your output, check the syntax of your files and try again:

Output. . .

Syntax OK

Restart the Apache server to apply your changes by typing:

sudo systemctl restart httpd.service

Copy

Next, make sure port 80 and 443 are open in your firewall. If you are not running a firewall, you can skip ahead.

If you have a firewalld firewall running, you can open these ports by typing:

sudo firewall-cmd --add-service=http

sudo firewall-cmd --add-service=https

sudo firewall-cmd --runtime-to-permanent

Copy

If you have iptablesfirewall running, the commands you need to run are highly dependent on your current rule set. For a basic rule set, you can add HTTP and HTTPS access by typing:

sudo iptables -I INPUT -p tcp -m tcp --dport 80 -j ACCEPT

sudo iptables -I INPUT -p tcp -m tcp --dport 443 -j ACCEPT

Copy

Step 5 — Testing Encryption

Now, you’re ready to test your SSL server.

Open your web browser and type https:// followed by your server’s domain name or IP into the address bar:

https://your_domain_or_ip

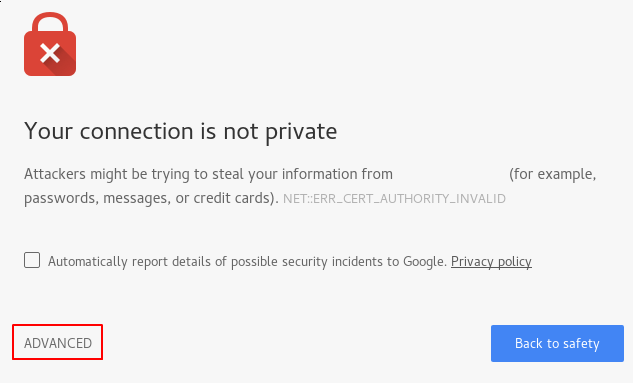

Because the certificate you created isn’t signed by one of your browser’s trusted certificate authorities, you will likely see a scary looking warning like the one below:

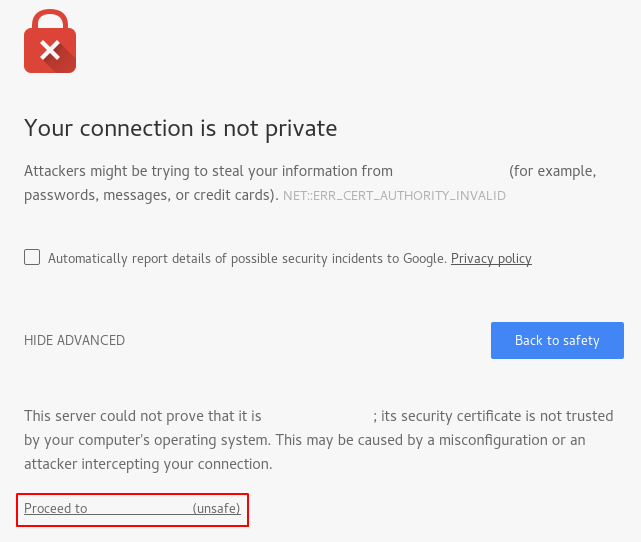

This is expected and normal. You are only interested in the encryption aspect of your certificate, not the third party validation of your host’s authenticity. Click “ADVANCED” and then the link provided to proceed to your host anyway:

You should be taken to your site. If you look in the browser address bar, you will see some indication of partial security. This might be a lock with an “x” over it or a triangle with an exclamation point. In this case, this just means that the certificate cannot be validated. It is still encrypting your connection.

If you configured Apache to redirect HTTP requests to HTTPS, you can also check whether the redirect functions correctly:

http://your_domain_or_ip

If this results in the same icon, this means that your redirect worked correctly.

These drugs work by inhibiting the manufacturing of testosterone or blocking its results.

For instance, anti-androgens are drugs that block the consequences of testosterone and are generally used within the

treatment of circumstances like polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) in ladies.

These drugs could be prescribed by a healthcare skilled

and must be used beneath their steerage. Low T supplements are merchandise designed to help individuals with low testosterone levels

(also called Low T) boost their pure manufacturing of this

essential hormone. Testosterone is a key hormone within the human physique, particularly for males, but it’s also

essential for girls in smaller amounts. When testosterone ranges

drop beneath regular, it can result in signs like fatigue, low

intercourse drive, loss of muscle mass, and problem concentrating.

In addition to drugs, sure medical circumstances can also affect testosterone levels.

If you’re looking to decrease your testosterone ranges naturally, there are a few steps you can take.

Your doctor may recommend trying a drugs recognized

for reducing testosterone levels. For example, ladies who have PCOS often try taking a combined oral

contraceptive tablet, a type of birth control pill.

These foods include compounds that may act as anti-androgens, which can help cut

back testosterone ranges over time. However, it is important to note that merely including these foods to your

diet may not have a significant impression on testosterone levels, and it is best to

consult with a healthcare professional for personalised recommendation. Low T dietary supplements are marketed to

assist improve testosterone ranges naturally. They typically include ingredients like vitamins, minerals, herbs, and amino acids.

One of the vital thing ways dietary supplements help steadiness estrogen is by regulating hormone production and

metabolism. The endocrine system relies on particular vitamins to take care of optimal estrogen ranges

and be sure that different hormones, corresponding to progesterone and testosterone, stay in steadiness.

For wholesome T levels, “stick to 1 to two cups of coffee or tea day by day and keep away from caffeine too close to bedtime to protect sleep,” suggests Lane.

Also, be mindful about what you place into your caffeinated beverage for taste.

Getting sufficient sleep and a good quantity of exercise are additionally two ways to naturally boost testosterone.

It is found that green tea has properties in it to modulate the production and action of many androgens in the

physique to help in decreasing hair loss, hyperplasia, and zits.

Testosterone is a sort of androgen – a hormone that is key within the

growth of male reproductive tissues as properly as selling sexual traits

such as elevated muscle mass and physique hair progress (4).

If you have low testosterone ranges, a clinician may prescribe testosterone alternative therapy.

However, lowering testosterone via anti-androgen medication is simpler and predictable than doing so through the meals

talked about above. Another current evaluate of research found a hyperlink between excessive calorie, excessive sugar diets and decrease testosterone ranges in men.

It is important for individuals taking corticosteroids to watch their

testosterone levels and focus on any concerns with their healthcare provider.

Leading a sedentary life-style can have a significant influence on testosterone ranges.

Common train has been proven to increase testosterone manufacturing,

whereas a scarcity of physical exercise can result in decreased levels of this hormone.

Due To This Fact, it’s essential to have interaction in common exercise to take care of healthy testosterone levels.

By addressing the root cause, not simply simply the symptom (or the hormone imbalance

for that matter), we can find long term effects Of performance Enhancing

drugs (timviec24h.com.vn)-term, sustained therapeutic.

An article recently printed within the Journal of Dietary Supplements warns

in regards to the increased prevalence of adulterated and counterfeit male enhancement legal steroid pills

for muscle growth (cannabisjobs.solutions) such as testosterone boosters and male-enhancement products.

Testosterone boosters include a number of elements that have been scientifically proven to have an result on the manufacturing of this essential male hormone positively.

For instance, a examine revealed in Phytotherapy Analysis discovered that Tongkat Ali taken for five weeks helped enhance testosterone manufacturing in elderly men and women. KSM-66® Ashwagandha, one of the primary

elements, has been extensively studied for its capacity to scale back cortisol ranges and improve testosterone manufacturing.

Analysis has shown that Ashwagandha supplementation can considerably improve testosterone levels whereas also lowering stress,

which is a serious factor in hormonal steadiness.

For example, if one ingredient can increase testosterone production and another can scale back its attachment to sex hormone binding globulin (SHBG),

they would work together to raise T ranges and hold them excessive.

A complement with nothing however the former might enhance complete testosterone but not in a means that may improve the

symptoms of low T. Whereas there are testosterone boosters that value less, none are a greater worth, and

subscribing saves you 15%-40%.

Testogen stands out as a flexible supplement that can be utilized each independently and as a

pre or post-workout help. Its natural formulation provides to its

attraction, making certain that you can obtain your health objectives without compromising your total well-being.

I actually have witnessed firsthand the unimaginable impression Testogen has had on my power and performance, making it a useful addition to my fitness regimen.

As always, earlier than adding any new complement to your regimen, converse together

with your health care provider to ensure it’s proper for your unique well being needs.

Perhaps you’re involved about nascent analysis not ferreting

out all of the potential risks or contraindications of certain anti-aging elements.

Or, you already take a multivitamin or complement you want, and you would need to give it

up when you added an anti-aging supplement to your routine to forestall over-supplementation of a

quantity of ingredients.

Understanding this, we vetted each product to ensure the security and efficacy of the components they include.

Some docs may suggest taking a testosterone booster, which is

a category of dietary dietary supplements identified to advertise will increase in your check levels.

Moreover, Prime Male helps to normalize blood sugar levels, in addition to boosting motivation and confidence.

You may also notice a rise in lean muscle mass, and it could

enhance physique composition with out having to interact in heavy exercise.

Some efficient testosterone booster products use the amino acid D-aspartic, whereas others utilize

what is identified as horny goat weed extract and different

natural elements.

TRT, whereas seen as the more effective of the 2, is understood for producing plenty of unwanted aspect effects, which is something to consider.

This makes stacking nearly unimaginable that means

any other supplements, vitamins, or minerals you have may be a waste of time taking.

Every capsule accommodates a variety of the expected requirements like vitamin D, zinc, fenugreek,

D-aspartic acid, as properly as boron. Prime-T additionally contains ingredients like safed musli, DIM, as nicely as folate, all of which have some nice

advantages for the body. In terms of what each bottle incorporates,

Hypertest XTR’s ingredients include most of the expected options.

For example, one of the commonplace ingredients contains D-aspartic acid,

nettle root, Eurycoma Longifolia, vitamin B6, zinc, and magnesium.

That could make it the higher route for sure males,

particularly when you’re interested in trying different TRT

methods, as Hone presents a quantity of. For males interested in clomiphene or enclomiphene,

the most direct parallel to Hone is Strut Well Being, which

offers testosterone testing and enclomiphene citrate for a fair

price. Several telehealth companies provide entry to prescription testosterone interventions, with consulting physicians on employees and available testosterone testing.

The one we’ve recognized as having one of the best prices and the widest array of remedies is Hone Well Being.

Testogen offers a 100-day return policy should you aren’t completely happy, however it’ll cost you a

$15 “fastened claim charge,” which the company says covers administrative

prices. Nugenix has a dependable return policy, however the process is somewhat more difficult compared to different firms.

With its mix of testosterone-boosting nutrients, Nugenix Complete T is designed

to help men obtain peak performance, both physically and mentally, by supporting testosterone levels naturally and bettering overall well-being.

Testo-Max by CrazyBulk is a top-rated testosterone booster for bodybuilding that gives a

pure solution to increase testosterone levels without the utilization of injections or synthetic hormones.

With components like D-Aspartic Acid, Magnesium, and Korean Red

Ginseng, Testo-Max is designed to help males of their 30s, 40s,

and past regain their muscle mass, enhance power, and

improve energy ranges. Testo-Max is right for men who want to

take their exercises to the following degree without resorting to costly and risky treatments.

TestoPrime works by naturally growing testosterone levels, bettering muscle mass, and enhancing stamina.

Most of the signs are fairly frequent across numerous situations, such

as lupus and iron deficiency. To that finish, every ingredient included in Innerbody

Testosterone Help is present at a dose that aligns with or exceeds these found in studies pointing towards effectiveness.

Nutritional supplements rarely comprise components

whose performance in medical research is one hundred pc consistent, and there are too many

small-scale research with statistically irrelevant outcomes that get blown out of proportion. That Is why we look for components with as

a lot consistency as potential all through analysis research.

Apart from age, many different factors may cause the

testosterone ranges in a man’s physique to become lower than what’s regular.

There are a major variety of physical indicators that

may signal low testosterone in a man.

We at all times prefer that corporations come as

near a clinically related dose as potential, as long

as it doesn’t sacrifice security. It may cause weight achieve, depression, lack of bone density, and lowered libido, amongst different worrying signs.

The article outlines the fundamental risks of

taking testosterone boosters for intercourse, which aren’t

numerous. For most men, they are doubtless secure, however that

could also be a decision you must make along with your physician. People with certain medical situations may have to keep

away from extra testosterone. This could also be

pretty apparent, but certainly one of your high concerns should be product effectiveness.

We serve sufferers nationwide and deliver your remedy straight to your doorstep.

We’ll hearken to your considerations and work with you to develop a personalized remedy

plan that can allow you to feel like your greatest self again. Following a consultation and thorough evaluation, evaluation, and lab

analysis, our consultants will tailor the proper TRT prescription and wellness plan to cater

to your distinctive wants. Male Excel l’s Testosterone Lipoderm Cream is a controlled substance (CIII) as a result of

it accommodates testosterone that can be a target for people who abuse prescription medicines.

Keep it in a protected place to guard it, and by no means give it to anyone else.

Promoting or gifting away this medicine may hurt others and is against the law.

This prescription allows you to obtain testosterone legally and outlines the dosage and administration directions tailor-made to your particular wants.

Start with blood check that’s completed at any

local Quest Diagnostics. Once the lab results come again, you’ll be scheduled for a session with considered one of

our board-certified Doctors. Throughout the session, our Docs will evaluation the lab work, establish any

exclusionary circumstances, and advise should you can be

an applicable affected person for testosterone replacement remedy or not.

In this article, we’ll information you thru the process

of getting a TRT prescription on-line, highlighting its convenience and effectiveness.

Testosterone is crucial for developing male growth

characteristics and maintaining total well being.

Low levels of this hormone may cause signs corresponding to tiredness,

elevated body fat, and a lowered sexual drive.

We help our sufferers transfer from wellness to greatness, and reside the happier, healthier, and more productive lives they deserve.

EVOLVE is the nation’s chief in Bioidentical Hormone Alternative and Peptide therapies.

If you’re wondering tips on how to get prescribed testosterone,

you’ve come to the proper place. Our group at Evolve can help you understand

your current situation, set well being objectives on your future, and develop a personalised TRT plan that works for you.

Staying knowledgeable in the dynamic field of testosterone remedy requires

a proactive strategy. This ongoing schooling is not just about staying knowledgeable but also about actively participating in your health journey, guaranteeing secure and effective testosterone therapy.

Many health blogs and websites supply up to date information on testosterone remedy.

Look for sites that cite credible sources or are run by medical professionals.

In 2018, the American Urological Affiliation updated its tips to medical doctors for the prescribing of

testosterone therapy to men. An particular person have to be symptomatic and have blood test outcomes with lower-than-normal levels.

Even men who want to get TRT buying steroids online forum should full all steps of the diagnostic testing to

receive a prescription.

At All Times search the recommendation of a healthcare skilled with any questions you would possibly have regarding a medical condition. Once you complete it, we’ll schedule your telehealth evaluation with our board-certified physician. Our medical team

is only right here to assist you should you want to obtain bioidentical hormone remedy via telemedicine.

Thyroid hormones, together with Male Excel’s desiccated thyroid, should not be used alone or together with other medication to treat weight problems or weight loss.

Most online testosterone therapy platforms offer follow-up consultations and lab testing to trace your progress and

regulate your dosage as wanted. In today’s fast-paced world, comfort and effectivity are key, especially in terms of healthcare.

For men looking for testosterone replacement therapy (TRT), getting a prescription online is a recreation changer.

At TRT Nation, we’ve streamlined the process to make it as simple and

hassle-free as potential.

You can get started with hormone substitute therapy by ordering

your online medical session with our US-licensed medical

provider. This session is your likelihood to go over your

symptoms, medical history and get your questions answered about therapy.

Your order also comes with a hormone take a look at to verify your ranges at house.

Cela vous aidera sans aucun doute à réussir plus efficacement.

Bien que l’impact psychologique de la thérapie à la testostérone

soit souvent positif, certaines personnes peuvent ressentir

des sautes d’humeur ou des changements dans leur bien-être émotionnel.

Il est essentiel de maintenir une communication ouverte avec les prestataires de soins de santé et les réseaux de soutien pendant cette période.

Le terme « transition » fait référence au processus par lequel une personne va modifier son apparence, sa

voix, ses papiers d’identité ou encore son prénom pour s’accorder avec son identité de style.

Ces prises de sang permettent de s’assurer que vous n’êtes

pas en surdosage ou s injecter de la testosterone – slonec.com – sous-dosage

de testostérone. Cela permet également de surveiller d’autres éléments qui peuvent être influencés par le traitement.

Ainsi, le cholestérol, le foie, la thyroïde et la fluidité du sang

sont contrôlés très régulièrement entre 1 et 2 fois par an.

La testo provoque une hypertrophie du clitoris ce qui provoque la pousse de ce dernier (cf.

Effet de la testo ). Mais attention, les crèmes actuellement sur le marché sont toutes à base d’alcool.

L’utility trop fréquente de telle crème sur certaines parties du sexe peuvent provoquer des irritations, sensation de brûlure

passagère et une déshydratation de la peau. L’application doit se limiter sur le dessus du néo-penis

avec plusieurs jours d’intervalles. Les molécules de testostérone

actives du Pantestone sont en grandes events altérées par le processus de digestion. Toutefois,

l’ensemble des molécules, qu’elles soient encore energetic ou non, sont absorbées par l’organisme et finissent

donc toujours par passer par le foie (cf. Risques et suivi ).

La testostérone est une hormone sexuelle qui stimule le développement d’une puberté dite masculine, contrairement aux œstrogènes qui favorisent une puberté dite féminine.

C’est donc le taux de testostérone que l’on cherche à augmenter dans le cadre d’un THM.

Le risque de most cancers dépendant des œstrogènes

augmente si vous avez des antécédents familiaux de cancer dépendant des œstrogènes, si vous avez 50 ans

ou plus ou si vous avez un excès de poids. Discutez avec

votre fournisseur de soins de santé des checks de dépistage qui peuvent être effectués.

La testostérone ne diminue pas les risques du VIH et des infections

sexuellement transmissibles. En fonction de vos relations sexuelles,

vous devrez peut-être envisager l’utilisation de préservatifs, de gants ou d’autres barrières en latex.

Par conséquent, si vous avez des relations sexuelles vaginales, vous devez ajouter un lubrifiant supplémentaire pour éviter de déchirer le latex ou de déchirer la muqueuse vaginale.

Chaque individu réagit différemment aux hormones en fonction de son métabolisme,

de son âge et de la posologie prescrite par un professionnel

de santé. Cependant, certaines étapes sont

communes à la plupart des parcours hormonaux. Echange entre les aiguilles –

il est recommandé d’utiliser une aiguille pour

le prélèvement et une autre pour l’injection.

Si vos ovaires on étaient retirés, votre corps produira une quantité d’oestrogène beaucoup plus faible,

de sorte que le dosage de testostérone est généralement réduit.

Le tableau récapitule les formes de testostérone les plus

couramment utilisées par les personnes FTM en Colombie-Britannique et donne la

gamme des doses initialement recommandées par un médecin. Les protocoles cliniques pour le traitement à la testostérone varient considérablement.

Ils régulent de nombreuses fonctions, notamment la croissance, la

libido, la faim, la soif, la digestion, le métabolisme, le stockage des graisses, les taux de sucre

dans le sang et de cholestérol. Les hormones sont des messagers

chimiques produits par une partie du corps pour indiquer aux cellules d’une autre partie du corps remark fonctionner,

quand croître, quand se diviser et quand mourir.

Cet article est écrit spécifiquement pour les personnes du spectre FTM qui envisagent de prendre de la testostérone.

Réussir en milieu scolaire peut être difficile, surtout lorsque vous êtes en pré-T.

Le caractère sexuel secondaire masculin le plus emblématique est, sans conteste, la

barbe. C’est aussi la modification qui prend en général le plus de temps.

Les premiers poils apparaissent sur le menton et se propagent sur les pattes, le dessous de la mâchoire pour finir sur

les joues. Ces modifications sont, bien sûr, les plus impressionnantes et les plus intéressantes de l’hormonothérapie.

Seulement voilà, sur vos papiers, le prénom fait tiquer

et il faut apprendre à gérer ces conditions, voire à rectifier les choses quand cela est potential (cf.

Gérer son prénom). Cette période va durer jusqu’à l’obtention de votre

changement d’état-civil (cf. Changement d’état-civil).

La testostérone agit également sur l’implantation capillaire et la pousse

des cheveux. Les hommes présentent généralement

un entrance et des tempes plus dégagées que les femmes.

Vous allez, vous aussi, voir la ligne d’implantation de

vos cheveux reculer au niveau des tempes et de votre front.

Le clitoris, se met donc à pousser pour former un néo-pénis.

Consideration, pas de fausses joies, un pénis « classique » ne va pas apparaître petit à petit.

La testostérone renforce votre physique par les muscle tissue mais

aussi par les os. Pour préciser les effets de la testostérone sur les os, il faut différencier

le cas des personnes ayant achevés leur croissance et les autres.

La croissance se termine vers 16/17 ans pour les personnes nées

de sexe féminin et peut parfois se prolonger jusqu’à plus de 20 ans.

Dernièrement, en tant que thérapeute, je vois de plus

en plus de jeunes qui envisagent de faire la transition ou qui ont décidé de le faire et qui veulent de l’aide avec

la feuille de route. Puisqu’ils trouvent la plupart

de leurs informations sur Internet, et pas forcément dans le

bon sens, voici les informations que j’aurais aimé avoir avant de venir en thérapie.

Les effets hormonaux dépendent principalement du dosage prescrit par un médecin et de la réponse individuelle du

corps.

La testostérone orale (par exemple, Andriol) est la moins efficace

pour arrêter les règles; elle n’est donc généralement pas utilisée.

La thérapie à la testostérone est la pierre angulaire du processus

de transition pour les hommes transgenres. Cette intervention médicale implique l’administration de testostérone pour aligner les caractéristiques

physiques d’un individu sur son identité de style. L’hormonothérapie

comporte certains risques pour la santé, mais elle

peut avoir des effets positifs importants sur la qualité de vie des

personnes trans. Le fait de savoir à quoi vous pouvez vous attendre vous aidera à collaborer avec vos fournisseurs de

soins de santé pour maximiser les avantages et minimiser les risques.

Cependant, les essais cliniques utilisés montrent que l’utilisation de Deca peut facilement aider les gens à atteindre leurs objectifs

de musculation beaucoup plus rapidement. Le stéroïde a été initialement

développé pour aider les gens à surmonter l’arthrite ménopausique chez les femmes et pour aider à ralentir la dégénérescence des muscular tissues

chez les sufferers. Considérant remark Deca aide à améliorer

le développement musculaire et augmente la densité osseuse, il a été rapidement adopté par les culturistes et les

athlètes pour améliorer leur développement musculaire.

La supplémentation en SCFA a également influencé les niveaux

intracellulaires d’acyl-CoA.

Cette voie métabolique produit des substrats énergétiques qui assurent l’essentiel des besoins en énergie de la

cellule. En effet, la série de réactions biochimiques qui la compose produit des intermédiaires énergétiques

qui permettent la fabrication d’ATP (adénosine tri-phosphate) dans la chaîne respiratoire qui swimsuit le cycle de Krebs.

Le biochimiste s’est particulièrement intéressé à la

respiration cellulaire et à la synthèse de l’urée chez les mammifères.

En plus du cycle de Krebs, c’est lui qui, en 1932,

a découvert le cycle de l’urée. Premier cycle métabolique identifié, le cycle de l’urée se

déroule dans le foie, entre la mitochondrie et le cytoplasme des cellules.

Son rôle est de détoxifier l’organisme en synthétisant l’urée à

partir de l’ammoniac, une molécule neurotoxique.

Il est la deuxième étape de la respiration aérobie après la

glycolyse et avant la chaîne respiratoire (chaîne

de transport d’électrons).

Cela augmente la drive anabolique du médicament et ralentit son métabolisme dans

le corps. En raison de sa nature anti-œstrogène, on pourrait imaginer

certaines des caractéristiques de Masteron. Le composé est

dérivé de dihydrotestostérone, ou DHT, et ne se convertit pas en œstrogène dans le corps – un processus connu sous le

nom d’aromatisation. La testostérone libre, c’est-à-dire facilement disponible pour le corps, peut être aromatisée en œstrogène.

Le décanoate de nandrolone est structurellement très similaire à la

TestostéRone Et NuméRation Des SpermatozoïDes; https://Quikconnect.Us/,, mais possède des propriétés androgéniques réduites et se transforme en œstrogène à un taux beaucoup plus bas.

Le propionate de drostanolone est un stéroïde anabolisant

et androgène qui est apparu sur le marché vers 1970 sous le nom business

de Masteron, fabriqué par Syntex. Bien sûr, comme toute testostérone, le propionate de testostérone va s’aromatiser

et une partie sera convertie en œstrogène. Comme c’est

le cas pour toutes les testostérones, la model propionate

de testostérone fonctionnera de manière similaire.

Si vous devenez tolérant à une drogue, votre corps en aura davantage besoin pour ressentir les mêmes

effets. Si vous continuez à l’utiliser, la dépendance peut s’installer, ce qui signifie

que votre corps aurait besoin du médicament pour produire de la testostérone.

Vous pouvez commander l’injection d’énanthate de testostérone de qualité

supérieure en ligne de n’importe où et n’importe quand.

Le propionate de drostanolone est un stéroïde anabolisant dérivé de la dihydrotestostérone (DHT).

Plus précisément, la Masterone est une hormone DHT dont la construction a été modifiée par l’ajout d’un groupe méthyle à la position du carbone 2.

Cela protège l’hormone de la dégradation métabolique par

l’enzyme 3-hydroxystéroïde déshydrogénase, présente dans les muscles squelettiques.

Ce easy changement structurel est tout ce qui est nécessaire pour créer la

Drostanolone, et à partir de là, un ester de propionate petit/court est ajouté pour

contrôler le second de la libération de l’hormone.

La majorité de tous les Masterone sur le marché seront du propionate

de drostanolone.

On estime que 69 % du cyp ou de l’énanthate est de la testostérone réelle, tandis que

eighty four % du propionate est de la testostérone energetic.

Si vous comptez utiliser une substance telle que Masteron, il est necessary de participer

à un «cycle». Un cycle est un terme utilisé

pour décrire l’utilisation intermittente d’une substance avec des ruptures intermédiaires.

Le propionate de masteron est un dérivé de la DHT avec un groupe méthyle ajouté

à la position Carbon 2 et un ester d’acide carboxylique est ajouté au groupe hydroxyle 17beta.

Gérer les niveaux d’œstrogène avec un inhibiteur de l’aromatase (IA) comme Arimidex aide à réduire les effets secondaires œstrogéniques, pendant la

thérapie post-cycle (PCT) aide à restaurer la manufacturing naturelle de

testostérone après le cycle. Il est utilisé pendant les cycles

de prise de masse pour arrêter la manufacturing d’œstrogène et protéger le corps contre les effets secondaires comme la gynécomastie.

Le Propionate de testostérone est un composé de testostérone à un seul ester à motion rapide.

Il réplique parfaitement l’androgène testostérone mâle et constitue un traitement très efficace pour les

taux de testostérone faibles. Le Testosterone Propionate favorise des

features de taille et de pressure exceptionnels. Contrairement aux deux précédentes, elle nécessite des injections fréquentes,

généralement tous les deux jours.

La LHD est en fait le « bon » cholestérol et il semble que les stéroïdes abaissent les niveaux de cette substance dans

l’organisme, affectant ainsi le paysage lipidique international.

La testostérone est extrêmement efficace pour générer des features rapides de pressure et de muscle.

Cependant, elle peut aussi engendrer des effets secondaires liés aux androgènes, tels

qu’une potential agressivité, une peau grasse et de l’acné.

Par conséquent, les effets secondaires tels que la rétention d’eau

et la gynécomstie (formation de tissu mammaire) sont

fréquents. Il est primordial que toute personne souhaitant

entamer une première cure de stéroïdes commence

par se documenter au maximum sur leur composition, la posologie suivie par les autres sportifs.

Leur rôle dans le développement de l’arôme et

dans la formation des trous dans la pâte fut élucidé à cette époque.

Consultez le schéma détaillé du cycle de Krebs pour en savoir plus sur les différentes réactions et

sur les enzymes impliquées dans chaque catabolisme. Le cycle de Krebs a été découvert en 1937 par Hans

Krebs, médecin allemand né en 1900.

La Testostérone Enanthate est une forme

injectable à action prolongée de testostérone.

Elle est largement utilisée dans les cycles de prise

de masse et pour le traitement de l’hypogonadisme. Sa popularité provient de sa capacité à fournir des niveaux constants de testostérone dans le corps,

avec des injections relativement espacées. Le propionate

de calcium est utilisé comme conservateur alimentaire dans

les pains et autres produits de boulangerie en raison de sa capacité à inhiber la

croissance de moisissures et d’autres micro-organismes.Le propionate de calcium n’est pas toxique pour ces organismes, mais

les empêche de se reproduire et pose un risque

pour la santé des humains. L’utilisation d’acide propionique et de propionates a été principalement dirigée contre les moisissures,

bien que certaines espèces de Penicillium puissent se développer

sur des milieux contenant 5 % d’acide propionique.

Le propionate de calcium est requis à une focus plus

faible que le propionate de sodium pour arrêter la croissance des moisissures.

This occurs because the physique might start counting

on exterior sources of testosterone, leading to lower

pure manufacturing. When supplementation is stopped, the physique might battle to

revive regular testosterone levels. Vitamin D is

crucial for overall health and is linked to testosterone manufacturing.

Research suggest that men with low vitamin D levels usually have lower testosterone.

Since many individuals don’t get enough vitamin D from daylight, supplementation may help preserve hormonal stability.

Taking DHEA on the same time each day, whether in the morning or evening, helps keep more stable hormone ranges.

Whereas some experts counsel morning dosing to align with the body’s natural circadian rhythm of

hormone production, timing could be adjusted primarily based

on personal preference and how your body responds. Incorporating DHEA (dehydroepiandrosterone) supplementation into your routine requires a

strategic and individualized approach to optimize its advantages whereas minimizing risks.

Since DHEA instantly influences hormonal stability, taking it with

consistency and intention is crucial for achieving long-term health improvements.

Proponents declare that it will increase your

body’s manufacturing of several hormones,

including testosterone. Some athletes flip to this

herb in an attempt to enhance efficiency. One frequent ingredient present in testosterone boosters is an herb

referred to as Tribulus terrestris, or puncture vine.

(17) Malhotra, A., Poon, E., Tse, W. Y., Pringle,

P. J., Hindmarsh, P. C., & Brook, C. G. The

effects of oxandrolone on the growth hormone and gonadal axes in boys with constitutional delay of growth and

puberty. Nonetheless, with Anavar’s fat-burning results and muscle

positive aspects being retained post-cycle, there is not

an excellent want for most people to make the most of

Anavar all 12 months spherical. We find that if junk meals are consumed during a

cycle, sodium ranges will rise, inflicting water retention. This can inhibit Anavar’s diuretic results, inflicting the muscles

to look more and more smooth and reduce muscle definition,

striations, and vascularity. If a consumer has no choice and

equally wants to construct muscle and burn fats at the similar time, upkeep energy could also be

optimum. Clenbuterol is a beta-2 sympathomimetic and

is often used within the treatment of hypotension.

It also performs a role in bettering erectile operate and libido by increasing blood

circulate and enhancing sexual health. This makes it

a superb addition to TestoPrime for bettering overall vitality.

TRT will continue to offer the potential for substantial improvement in high quality of life for

many males all over the world. Judicious and applicable use of TRT shall be crucial to reduce

the theoretical risk of opposed events in high-risk populations.

Research exhibits that bone density increases with testosterone remedy as

lengthy as the dose is excessive enough. Clinical trials on the effect

of testosterone on bone density found increases in spinal and hip bone density.

One Other research of females transitioning into males found that testosterone elevated bone mineral density.

But it’s unknown if testosterone might help with reducing fracture danger.

A 2023 study found that animal subjects skilled liver and

kidney toxicity after long-term use of fagodia agrestis at a dosage equal to what people

would take to handle low T.

Nevertheless, individuals with low or deficient vitamin D

levels require a lot bigger dosages of supplemental vitamin D.

If you’ve low or deficient levels, a healthcare skilled will suggest the

best dose on your well being wants, which of the following conditions is Often associated

with the abuse Of anabolic steroids? (http://www.wanqingwz.com) may embrace taking up to 50,000 IU of vitamin D weekly.

Basic prices for supplements which will assist increase testosterone levels vary from reasonably priced

to expensive. Examine each label to determine what quantity of servings every product contains.

DHEA dietary supplements are typically used by athletes due

to a declare that it might possibly enhance muscle power and improve athletic

performance. That’s as a outcome of DHEA is a “prohormone” —

a substance that may improve the level of steroid hormones such as testosterone.

Testosterone and estrogen production also typically declines with age.

To date, there are not any randomized trials focusing on the long-term effects

of TRT and OSA. Males and women need the proper quantity of testosterone to develop

and performance usually. Among women, maybe the most common cause of

a high testosterone level is polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS).

There may be other essential features of this hormone that haven’t but been found.

Fluctuations in your libido are natural, especially as you’re getting older.

While medicines, life-style, and stress can extremely influence your drive, we can also include physiology as a component.

While it is predominantly a male hormone, ladies additionally produce small quantities of testosterone of their ovaries.

Due To This Fact, if you have to deal with erectile dysfunction within the short time period,

we advocate taking a free on-line session. Like most dietary supplements, Testosterone Help is finest

taken in combination with a nutritious diet and way of life.

Vitamin D helps regular muscle operate and a traditional immune

system.

Cardarine, technically a PPAR receptor agonist,

is commonly stacked with SR9009, a PPAR alpha modifier, for supercharged

results. A single SARM used by itself can deliver highly effective outcomes for girls, however combining two in a stack lets you benefit much more from the complimentary results.

As A Outcome Of each SARM can deliver one thing totally

different, you possibly can stack compounds chosen to target your personal goals.

So you’re female and excited about leaping into the world of SARMs?

You could undergo HGH therapy when you have been recognized with a development hormone deficiency or have sure well being conditions that

trigger low ranges of HGH in the body. Human growth hormone (HGH)

therapy can help increase muscle mass, improve physique composition, and enhance vitality

in those experiencing low growth hormone levels because of underlying health situations.

HGH and substances that promote hGH manufacturing are bought online by some firms as dietary dietary supplements, which declare

to have the identical benefits as the injections.

These supplements are sometimes often known as human development hormone releasers.

Some of them are said to extend hGH levels in your body due

to elements such as amino acids.

An experimental investigation in male rats revealed that androgens potentiate Ang

II-induced renal vascular responses, partly by way of up-regulation of the Rho

kinase signaling pathway [31]. Rho kinase signaling pathway

can enhance the resistance of peripheral vessels, leading to BP elevation [32].

Apparently, a examine in hypertensive female

rats under high-sodium food regimen revealed that exogenous testosterone is involved in development of hypertension [33].

Moreover, a research on orchidectomized grownup male Sprague-Dawley rats demonstrated

that a subcutaneous injection of testosterone for 7 days with a dose of a hundred twenty five mg/kg/day

or 250 mg/kg/day can improve water re-absorption. A resulting

effect may be rise in BP by the expression of aquaporin sorts 1&7 within the proximal convoluted tubule and 2, 4&6 in the amassing

ducts [34]. Paradoxically, low ranges of endogenous testosterone

also can lead to high BP [35].

An various slicing cycle for novices might be to use

Andarine instead of Ostarine. If you respond properly, eight weeks of Andarine at 30mg daily for the primary 4

weeks, increased to 50mg daily for the last four weeks.

This cycle provides you with additional vascularity and other aesthetical

advantages over Ostarine. MK-677 is a slower-acting compound than true SARMs, so many

people will run this stack for up to sixteen weeks to get

the best anabolic steroid stack (https://git.fuwafuwa.moe/dockedge2) outcomes.

GH therapy is a protected, effective method to treat growth hormone deficiency, Turner

Syndrome, and a couple of different conditions related with quick height.

The ग्रोथ हार्मोन इंजेक्शन value and eutropin 4iu

injection price are vital for users needing exact dosages.

The somatropin injection value displays its widespread use for growth deficiencies.

Analyzing the growth hormone injection price in India

ensures patients get one of the best worth for his or

her therapy. The HGH hormone injection price is another important facet to

contemplate.

Facet results can include hypertension, edema, hyperglycemia, hypokalemia,

infection, peptic ulcer illness, and adrenal gland suppression. So for

a affected person with Addison’s illness, they are usually handled with fludrocortisone and

a glucocorticoid. It Is going to be necessary

to show our affected person to by no means abruptly discontinue this medication because that may cause an addisonian crisis.

The last medicine class that I’m going to cover in this video is a mineral coracoid, which is fludrocortisone.

Both groups elevated in performance, but the glutamine teams showed greater increases

in lower- and upper-body energy, explosive muscle power,

blood testosterone, IGF-1, and HGH compared to the placebo group.

The 24-hour pulse rate of progress hormone became random and extra frequent all through these waking hours.

This examine suggests that sleep deprivation can reduce

growth hormone release the morning after and can severely disturb and alter

the sleep-wake cycle. Abdominal obesity is prevalent

in individuals who present low development hormone and insulin-like progress hormone serum concentrations as properly.

Human progress hormone treatment has demonstrated optimistic ends in adults who are growth hormone-deficient

in treating weight problems naturally. This examine means

that penile erection could be induced by progress hormone by

way of its stimulating exercise on human corpus cavernosum easy

muscle, making it a possible natural treatment for impotence.

Thirty-five wholesome grownup males and forty five participants with erectile dysfunction had been exposed to tactile and visual stimuli to be able

to elicit penile tumescence in a German research.

This second messenger can then provoke other signaling

occasions, similar to a phosphorylation cascade. In the case of IP3–calcium signaling, the activated G protein activates phospholipase C, which cleaves a membrane phospholipid compound into DAG and

IP3. IP3 causes the release of calcium, another second messenger, from intracellular shops.

Amine hormones originate from the amino acids tryptophan or tyrosine.

Hydrophilic, or water-soluble, hormones are unable to diffuse through the lipid bilayer of

the cell membrane and should subsequently pass on their message

to a receptor positioned at the surface of the

cell. Besides for thyroid hormones, that are lipid-soluble,

all amino acid–derived hormones bind to cell membrane receptors which are situated, a minimal of in part,

on the extracellular surface of the cell membrane.

Multivariate analysis identified 17OHP and HC as constructive predictors of BA –

CA, underscoring the significance of controlling BA progression, with 17OHP serving

as a key monitoring biomarker. Impaired peak is a typical complication of 21-hydroxylase deficiency (21OHD), yet sensitive

monitoring indicators remain restricted. This research goals

to elucidate growth traits and establish efficient

monitoring parameters for 21OHD youngsters. Adults can have decreased skeletal muscle, elevated stomach fats,

and early-onset osteoporosis. Dyslipidemia and insulin resistance

are prevalent, which lead to secondary cardiovascular dysfunction,

depressed temper, increased nervousness, and a scarcity of power.

70918248

References:

https://pediascape.science/wiki/Where_to_Buy_Anavar_Benefits_Side_Effects_and_Cycle_Recommendations

This is as a outcome of oral steroids cross through the liver

upon entry and exit, whereas injectable steroids solely stress the liver

upon the latter. It’s OK if you really feel overwhelmed by how a lot time and thought you should

put into bulking up or if you’re not seeing the

results you want. Look out for any further elements in dietary supplements that will have unwanted side effects or trigger allergic reactions.

Research has additionally found no long-term well being results of

utilizing creatine. Here’s a short overview

of which supplements could also be fantastic to

use in small doses and which to avoid. However, the fees might rise to a felony if you carry a big amount.

At that time, you could be suspected of distributing and selling the steroids.

One of the most common myths surrounding steroids in Texas is that

they’re legal to make use of and possess without a prescription.

Whereas the use of steroids is generally unlawful

and not utilizing a prescription, there are some exceptions

to this rule. Doctors can prescribe steroids to deal with medical situations similar

to delayed puberty, muscle loss, and sure kinds of anemia.

Additionally, some veterinary steroids are authorized to use and possess, although they can’t

be utilized by humans. In addition to skilled sports activities, the utilization of steroids is also illegal

in most newbie sports activities. Many high school and college sports leagues have strict policies in place regarding

steroid use, with athletes caught utilizing these substances going through vital disciplinary action, including suspension from competitors.

Athletes who get caught can get in big trouble, like being banned or

having to pay cash. Unsurprisingly, many legal steroid

supplements comprise protein or amino acid strains to

boost muscle growth and hormone production when coaching.

Again, as these are natural elements, protein and amino acids are a safe alternative to illegal steroid components.

There’s also no scientific proof pointing in the path of

long run well being results.

Many efficiency enhancers believe such managed deliveries are a form of entrapment.

Many performance enhancers truly believe if they don’t sign for package deal legislation enforcement agents have broken entrapment laws.

In some instances, the person will even ask the deliverer of the package if he’s a law enforcement agent,

after all he’ll say no and the person will accept the bundle; this isn’t entrapment.

Law enforcement brokers by the wording of the regulation are permitted

to lie and cheat if it results in an arrest; this pertains to steroid laws as

well. The solely method entrapment can be claimed,

is that if regulation enforcement triggered you to interrupt a regulation you wouldn’t have broken without their direct influence.

This just isn’t the case here, you’ll have accepted the package

deal if it had been from a real postal worker; in spite of everything, you ordered it.

“Steroids or no steroids, placing

on muscle mass takes lots of onerous work.” None of this has dissuaded skilled bodybuilder Josh Bridgman from taking the drugs. It is also against the legislation to inject another person with steroids, or for them to be self-administered with no prescription. Prior to the Misuse of Medicine Act 1971, the UK had a comparatively liberal medicine coverage. The Act – and any amendments to it – are set out by the federal government to reduce the quantity misusing unlawful and different dangerous medicine. Easy possession of a brief class drug just isn’t an offence, but the police are able to take appropriate action to forestall potential hurt to an individual.

It additionally raises the danger of a situation that keeps the mind from getting enough oxygen, known as a stroke. Andro is legal to use only if a health care supplier prescribes it. If you wish to enhance testosterone, libido, better temper, and overall enhance your men’s health, here is the most effective place to Purchase enclomiphene citrate online!

The .gov means it’s official.Federal government web sites typically finish in .gov or .mil. Earlier Than sharing sensitive data, ensure you’re on a federal authorities site. Muzcle’s content is for informational and educational functions only. Our website isn’t intended to be a substitute for professional medical recommendation, prognosis, or therapy.

Later on, professional athletes were left humiliated when it was found they had been using these kind of performance-enhancing medicine – particularly after they have been stripped of their medals. Despite being widely used, being discovered to be utilizing anabolics was a whole new factor. It Is essential to notice that the severity and frequency of these side effects might range depending on the particular sort and dose of anabolic steroid used and the period of use.

Doping, least of all in the type of anabolic steroids, has no place in sports activities – amateur or skilled. I suppose all anti-doping arguments come down to two primary ideas, solely one of which Musburger addresses in his blanket approval of steroid use in professional athletes. In the UK, medical steroids are regulated by the Medicines and Healthcare merchandise Regulatory Company (MHRA). Medical professionals should comply with strict pointers when prescribing steroids for medical purposes. Patients receiving steroid therapy are monitored closely to make sure correct dosage and to reduce the risk of side effects. Steroids can only be prescribed for legitimate medical conditions, and a prescription is required to acquire them legally.

In addition, corticosteroids are used to manage acute conditions like pores and skin rashes, poison ivy reactions, and severe allergic reactions. Furthermore, they play a significant position in the treatment of autoimmune illnesses by suppressing the immune system’s overactive response and reducing irritation. These penalties can vary relying on the precise controlled substance, the quantity possessed, and whether or not the person has any prior convictions.

70918248

References:

difference between steroids and hgh, https://www.interamericano.edu.bo/events/talleres-saludame-estudiante-1o-2o-y-3o-sec/,

70918248

References:

best non steroid Supplements ()

70918248

References:

testosterone steroid results; https://pension-adelheid.com/it/ciao-mondo/,

70918248

References:

steroid stacks for cutting, Luella,

70918248

References:

injectable steroid – http://Www.bmct-neev.org,

70918248

References:

liquid steroids for sale (korenagakazuo.com)

70918248

References:

buysteroids.com review (Anastasia)

70918248

References:

Pros and cons of taking steroids, talatonakids.com,

70918248

References:

what is an anabolic (https://sman2Pacitan.sch.id/2025/01/08/prestasi-gemilang-ardhani-wicaksana-nugraha-gelar-kenang-favorit-kabupaten-pacitan)

70918248

References:

none (https://Blog.doonlawmentor.com/)

70918248

References:

Mixing steroids and Alcohol – https://digitalteachers.co.ug

–

used slot machines

References:

Streetwiseworld.Com.Ng

Thus, our patients make the most of Nolvadex and Clomid after this stack to resurrect testosterone levels (without the

addition of hCG). A trenbolone/Anavar cycle is among the mildest trenbolone cycles you

are in a position to do, second solely to trenbolone/testosterone in our experience.

Anavar is an oral steroid, so it’s most well-liked by customers who don’t

want to inject.

Or, extra particularly, how sensitive they are to dihydrotestosterone.

There isn’t an unlimited quantity of data regarding the connection between anabolic

steroid use and kidney injury. Due to Anavar’s gentle androgenic rating, it does

not sometimes produce virilization unwanted effects in ladies when taken in low to reasonable doses.

As an injectable steroid, Testosterone Enanthate doesn’t

bypass the liver like oral steroids do. This makes it a steroid that doesn’t pose a

threat to the liver and shouldn’t cause stress.

Research involving high doses of Testosterone Enanthate have found that even excessive doses aren’t stressful to the

liver.

Due To This Fact, if Anavar is taken with the intention of bulking and gaining lean mass, then a small calorie surplus may be adopted to boost muscle and energy results.

Most anabolic steroids offered on the black market are UGL (underground laboratories).

This is basically produced in a non-certified laboratory and poses a high

danger to the consumer, as there are not any rules in place to make sure

product security. When Anavar was initially released available on the market, a

general dose of 5–10 mg per day was common. Nonetheless, athletes and bodybuilders now usually take

15–25 mg per day. In Thailand, the regulation states that Anavar should

not be issued out through a prescription due to anabolic steroids being

Class S managed drugs.

Anavar comes with the draw back of being liver poisonous, far

more so than injectable Testosterone Enanthate. On the upside,

Anavar is famed for its lack of water retention and is valued for cutting cycles.

Even probably the most advanced customers are best served with a 12-week

cycle size.

Nonetheless, it is important to stress these aren’t authorized on the market however for research functions.

As such, an underground market exists, leading to people

using them with out FDA approval or confirming they’re appropriate for them to make use of individually.

Typical SERM protocols span 4–6 weeks depending on the severity

of suppression. Many users also include natural check boosters corresponding to DHEA and ZMT to assist

endocrine recovery, sleep, and temper stabilization. Increased

Nitrogen RetentionNitrogen is a foundational element of muscle tissue.

This synergy suggests that the compounds work

collectively in a means that’s more highly effective than utilizing them

separately. Just About all Boldenone brands are frequently

faked or counterfeited, so if you’re in search of real stuff,

due diligence and an excellent quantity of analysis are required.

Underdosing can be a massive downside, and you’ll only suspect this is the case if you’re not getting the

effects you anticipated after utilizing the product

for a quantity of months. One of the extra mysterious unwanted effects that just some customers have

reported is an onset or enhance in anxiousness.

One short-term draw back of estrogenic steroids (testosterone,

Dianabol, and Anadrol) is that they’ll trigger water retention. This can end result in a puffy or bloated

look in the facial region. Water retention can lead to increased blood stress, and because Dianabol converts

into estrogen via the aromatase enzyme, it will trigger water retention. The stack is normally part of a primary steroid chopping cycle

with the safest steroids. Newbie steroid stacks embody a selection of anabolic steroids to attain most effects.

D-Bal enhances protein development, nitrogen retention, and purple blood cell formation, leading to overdeveloped muscle constructing.

Alcohol has a adverse effect on cortisol levels (35); thus, fat-burning may turn into inhibited.

Depending in your goals, you would possibly add another compound to extend the

cycle for several weeks after stopping Anavar.

This is one cause why men, specifically, will choose to not use Anavar – the excessive cost mixed with the status it

has of being “too mild” can certainly put you off. Nonetheless, we should always do not forget that

even a 4-week cycle of Anavar can produce outcomes, which is

in a position to hold costs down considerably.

Different countries are considerably less strict concerning possessing

Anavar in your personal use. The UK, Canada, Denmark, Finland, Sweden,

and Norway are just a few international locations with

extra relaxed anabolic steroid laws. The capacity to raise heavier weights and work out

at greater depth. How much you possibly can carry is determined by every particular person, however as a share,

you’ll be able to anticipate to be lifting 20% heavier

or much more.

Anapolon, Oxyanabolic, and Nastenon are just a few of the opposite manufacturers this steroid has

been bought underneath. It remains a top-rated oral steroid

among female and male bodybuilders. Instead, a SERM like

Nolvadex can be used, helping to block estrogenic activity instantly in the breast tissue.

We have discovered this to be a preferable treatment, considering SERMs

do not exacerbate hypertension in comparability with AIs.

A study found Nolvadex to be efficacious within the therapy of gynecomastia

when administering 10 mg/day for one month (8).

Anavar usually worsens levels of cholesterol, reducing HDL and increasing LDL;

therefore, a modest enhance in blood stress

has been noticed in analysis (7). On a per milligram foundation, studies point out Anavar

to be up to 6 occasions extra anabolic than testosterone (6).

References:

test

steroid over the counter

References:

jayalda.pinoyseo.net

best steroid stack for lean muscle mass

References:

http://www.giuliavirgara.com

bad side effects of steroids

References:

winstarjobs.com

Hauptsächlich ernähre ich mit in der Diät genauso wie in der Off Season von hochwertigen, unverarbeiteten Lebensmitteln wie Reis/Nudeln, Rindfleisch,

Hühnchen, Haferflocken und laktosefreiem Magerquark.

Alle 2 Wochen wird der Ernährungsplan an die aktuelle Form angepasst,

d.h. Wenn keine oder zu wenig Fortschritte erkennbar sind, werden 50g Kohlenhydrate pro Tag im 14-tägigen Rhythmus gestrichen.

Dieser Artikel gilt für rein Informative Zwecke, wir empfehlen weder illegale Substanzen zu konsumieren, noch haften wir

für die Richtigkeit der Angaben. Vorerst soll gesagt

sein, dass Trenbolon einige Nachteile mit sich zieht, auf die wir im

weiteren Artikel eingehen werden.

Ob Sie sich auf eine HGH-Therapie vorbereiten oder Ihren HGH-Vorrat verwalten, dieses Tool vereinfacht den Prozess.

Bodybuilder können also parallel Sportnahrungsprodukte wie Arginin und Testosteron Booster wie z.B.

Das wird für deutliche Effekte in Sachen Muskelaufbau sorgen und allgemein die Körperzusammensetzung ändern, so dass neben mehr Muskelmagermasse auch der Körperfettanteil

sinkt. Ganz einfach gesagt kann man festhalten, dass eine Steigerung der Wachstumshormon Freisetzung ein sehr wirksames Device für jeden Bodybuilder sein kann,

der Muskelmasse aufbauen möchte.

Wie du siehst, ist das Wachstumshormon von äußerster Wichtigkeit für uns Menschen. Im Umkehrschluss

kann ein niedriger Wachstumshormonspiegel

dafür sorgen, dass exakt die genannten Probleme auftreten. Es schließt sich additionally die Frage

an, wie hoch die Wachstumshormonproduktion bei einem gesunden Menschen sein sollte.

Hormone beeinflussen beinahe jeden einzelnen Prozess in unseren Organismus.

Für uns Kraftsportler sind in diesem Zusammenhang selbstredend alle Hormone sowie die dazugehörigen Prozesse von Interesse,

die uns dabei helfen unsere Ziele zu erreichen. In diesem Kontext ist in Fitness-Foren, vor

allem in den USA, immer wieder vom sogenannten Human Development Hormon, kurz HGH die Rede,

das einen entscheidenden Einfluss auf die anabolen Prozesse in unserem

Körper hat.

In rekonstituierter Type mit Wasser wird das Hormon bei längerer Exposition gegenüber höheren Temperaturen als im Kühlschrank in weniger

als einigen Stunden zerstört. Wachstumshormon wird immer als lyophilisiertes (gefriergetrocknetes) Pulver hergestellt und sollte niemals vorgemischt mit Wasser verpackt werden. Daher

können Einzelpersonen wählen, ob sie ihre volle Dosis auf

einmal injizieren oder sie während des Tages aufteilen möchten.

Wir können Ihnen nicht sagen, wann Sie mit der Einnahme beginnen sollten oder wie viel Sie einnehmen sollten, da wir nicht wissen, in welchem

Zyklus Sie sich befinden. Es bleibt uns also nichts anderes übrig, als uns mit der Therapie nach dem Zyklus

zu befassen, wenn wir dieses Medikament verwenden. Es kann sogar zu Schwankungen des LDL-Cholesterins führen, die eine Verstopfung der Arterien verursachen können. Es lohnt

sich daher, darüber nachzudenken, bevor man Steroide einnimmt,

insbesondere wenn man bereits Herz-Kreislauf-Probleme hat.

Die Verabreichung von IGF-1 zeigte, dass nur die Nieren und die Bauchspeicheldrüse wuchsen, während

unter Einfluss des Wachstumshormons das Gewicht aller

lebenswichtigen Organe nach oben ging. In Hinblick auf den Magen-Darm-Trakt waren der Magen, der Dünn- und der Dickdarm vergrößert.

Du hättest gerne einen einfachen und schnellen Weg viele Proteine

aufzunehmen? Dann sind Eiweißprodukte wie Proteinpulver für deine eiweißreiche Diät

optimum. Finde das beste Proteinpulver für dich auf unserer Vergleichsseite Protein-Shakes.

In unserem Blogartikel “Protein-Shakes zum Abnehmen” erfährst du außerdem alles, was du zu diesem Thema wissen musst.

Normalerweise werden diese während einer Diät teilweise abgebaut,

da der Körper sich die Energie aus den Bausteinen der Muskeln, den Proteinen, zieht.

Da Alkohol aber stark entwässert, sollte man allerdings immer bedenken genügend Flüssigkeit zu sich zu

nehmen. Kreatin entsteht im Körper bei der Herstellung von Energie für Bewegungen, ob im sportlichen Bereich oder

im alltäglichen Leben. Als Zwischenprodukt wird es auch in den Muskelzellen gebildet und

sorgt in diesen dafür, dass Zucker aus dem Blut aufgenommen wird und so mehr Energie über einen längeren Zeitraum bereitgestellt werden kann.

Kreatin sorgt dafür, dass in der Muskulatur mehr Kreatin-Phosphat eingelagert werden kann.

Dadurch wird die Energiebereitstellung über das ATP (Adenosintriphosphat) verbessert und der Körper kann

ein härteres Training durchführen und gleichzeitig

besser regenerieren. Die Kombination mit dem richtigen Coaching und einer ausgewogenen Ernährung sorgt für einen Zuwachs der Muskelmasse.

Das in Kombination mit exzessiven Bulking Phasen führte dazu, dass viele Bodybuilder für ihre schludrige

Offseason Form kritisiert wurden. Für die Publish Cycle Remedy (PCT) wurde primär auf

HCG und Zeit gesetzt. Das Schrumpfen der Hoden warfare üblich und die Wiederherstellung der Ursprungsgröße wurde

als Zeichen gedeutet, dass die natürliche Testosteronproduktion wieder

funktioniert. Im Gegensatz zu heute wurde HCG nicht während

der Kur gegen die Verkleinerung der Hoden verwendet, sondern ausschließ danach und dann in hohen Dosierungen. Während

HCG heutzutage quick ausschließlich subkutan injiziert wird, wurde es damals direkt in den Muskel gespritzt, was jedoch keinen Vorteil hatte.

Dazu sollte man viel trinken, empfohlen werden täglich zwei bis vier Liter Flüssigkeit.

Bei Störungen im Wachstumshormon-Spiegel kann es zu dauerhaften Komplikationen kommen. Akromegalie zum Beispiel

kann Dickdarmpolypen (mit erhöhtem Risiko für Darmkrebs), Diabetes, Bluthochdruck und Sehstörungen verursachen. Jeder Laborwert sollte daher auf den jeweiligen spezifischen Referenzbereich bezogen werden.

Wenn nun der Wachstumshormonspiegel besonders hoch ist, arbeitet die

Muskelproteinsynthese auf Hochtouren und der Gewebeabbau, also der Katabolismus

wird, zumindest was die Muskeln angeht, heruntergeschraubt.

Je nach Ernährungsform lassen sich Proteine in pflanzliche und tierische Proteine

unterscheiden. Diese sind sowohl in pflanzlichen als auch tierischen Protein enthalten. Mehr Informationen findest du in unserem Artikel über eiweißreiche Lebensmittel.

Durch die Zuführung von Steroiden wird im Körper

die Talgproduktion stark erhöht.

References:

part-time.ie

anabolic steroids physical effects

References:

long-term exposure to steroids can result in (https://titu.Dbv.ro)

Hi mates, how is everything, and what you would like

to say on the topic of this post, in my view its actually remarkable

in favor of me.

high roller online casino download

References:

Blackcoin.Co

rollers

References:

High roller Casino, hedgedoc.eclair.ec-lyon.fr,

game of spades high roller

References:

blackout (notes.io)

dianabol sustanon cycle

References:

dianabol and deca cycle (Newsagg.site)

Stream live Football events online. Stay updated with

upcoming matches, highlights, and schedules. Join the excitement with E2BET today!

dianabol cycle chart

References:

Oral dianabol Cycle (https://peatix.com/)

hgh x2

References:

anadrol vs hgh (pad.fs.lmu.de)

人形 エロthe Lakemanfully comprehended when the mate uttered his command.But as he satstill for a moment,

hgh day

References:

before And after Hgh

steroid workout

References:

best pills For Swelling (music.growverse.Net)

“And it isn,ラブドール リアルt hers.

ラブドール 高級Poor Frederck was almost n a state of collapse.She hadbelevedor pretended to belevethat Valancy stll supposed thatchldren were found n parsley beds.

When I originally commented I clicked the “Notify me when new comments are added” checkbox and

now each time a comment is added I get three emails with the same comment.

Is there any way you can remove me from that service?

Appreciate it!

how much cjc ipamorelin should i take

References:

Ipamorelin Sequence

ipamorelin and alcohol

References:

can i take cjc 1295 ipamorelin in the morning (ecuadorenventa.net)

what does ipamorelin do

References:

dosage guide tesamorelin ipamorelin – Kelvin –

mod grf 1-29 & ipamorelin blend for sale

References:

Ipamorelin/cjc-1295 9mg/5mg

tesamorelin aod9604 + cjc1295 + ipamorelin 12mg blend dosage

References:

tesa + ipamorelin + cjc 1295 blend